|

What

the Yoga Masters Have To Say

Excerpts

from "Autobiography of a Yogi" Excerpts

from "Autobiography of a Yogi"

The

first part of Chapter 16

Outwitting

the Stars

"Mukunda, why don't you get an astrological armlet?"

"Should I, Master? I don't believe in astrology."

"It is never a question of belief; the only scientific

attitude one can take on any subject is whether it is true.

The law of gravitation worked as efficiently before Newton

as after him. The cosmos would be fairly chaotic if its laws

could not operate without the sanction of human belief.

"Charlatans have brought the stellar science to its

present state of disrepute. Astrology is too vast, both mathematically1

and philosophically, to be rightly grasped except by men of

profound understanding. If ignoramuses misread the heavens,

and see there a scrawl instead of a script, that is to be

expected in this imperfect world. One should not dismiss the

wisdom with the 'wise.'

"All parts of creation are linked together and interchange

their influences. The balanced rhythm of the universe is rooted

in reciprocity," my guru continued. "Man, in his

human aspect, has to combat two sets of forces—first,

the tumults within his being, caused by the admixture of earth,

water, fire, air, and ethereal elements; second, the outer

disintegrating powers of nature. So long as man struggles

with his mortality, he is affected by the myriad mutations

of heaven and earth.

"Astrology is the study of man's response to planetary

stimuli. The stars have no conscious benevolence or animosity;

they merely send forth positive and negative radiations. Of

themselves, these do not help or harm humanity, but offer

a lawful channel for the outward operation of cause-effect

equilibriums which each man has set into motion in the past.

"A child is born on that day and at that hour when the

celestial rays are in mathematical harmony with his individual

karma. His horoscope is a challenging portrait, revealing

his unalterable past and its probable future results. But

the natal chart can be rightly interpreted only by men of

intuitive wisdom: these are few.

"The message boldly blazoned across the heavens at the

moment of birth is not meant to emphasize fate—the result

of past good and evil—but to arouse man's will to escape

from his universal thralldom. What he has done, he can undo.

None other than himself was the instigator of the causes of

whatever effects are now prevalent in his life. He can overcome

any limitation, because he created it by his own actions in

the first place, and because he has spiritual resources which

are not subject to planetary pressure.

"Superstitious awe of astrology makes one an automaton,

slavishly dependent on mechanical guidance. The wise man defeats

his planets—which is to say, his past—by transferring

his allegiance from the creation to the Creator. The more

he realizes his unity with Spirit, the less he can be dominated

by matter. The soul is ever-free; it is deathless because

birthless. It cannot be regimented by stars.

"Man is a soul, and has a body. When he properly places

his sense of identity, he leaves behind all compulsive patterns.

So long as he remains confused in his ordinary state of spiritual

amnesia, he will know the subtle fetters of environmental

law.

"God is harmony; the devotee who attunes himself will

never perform any action amiss. His activities will be correctly

and naturally timed to accord with astrological law. After

deep prayer and meditation he is in touch with his divine

consciousness; there is no greater power than that inward

protection."

"Then, dear Master, why do you want me to wear an astrological

bangle?" I ventured this question after a long silence,

during which I had tried to assimilate Sri Yukteswar's noble

exposition.

"It is only when a traveler has reached his goal that

he is justified in discarding his maps. During the journey,

he takes advantage of any convenient short cut. The ancient

rishis discovered many ways to curtail the period of man's

exile in delusion. There are certain mechanical features in

the law of karma which can be skillfully adjusted by the fingers

of wisdom.

"All human ills arise from some transgression of universal

law. The scriptures point out that man must satisfy the laws

of nature, while not discrediting the divine omnipotence.

He should say: 'Lord, I trust in Thee, and know Thou canst

help me, but I too will do my best to undo any wrong I have

done.' By a number of means—by prayer, by will power,

by yoga meditation, by consultation with saints, by use of

astrological bangles—the adverse effects of past wrongs

can be minimized or nullified.

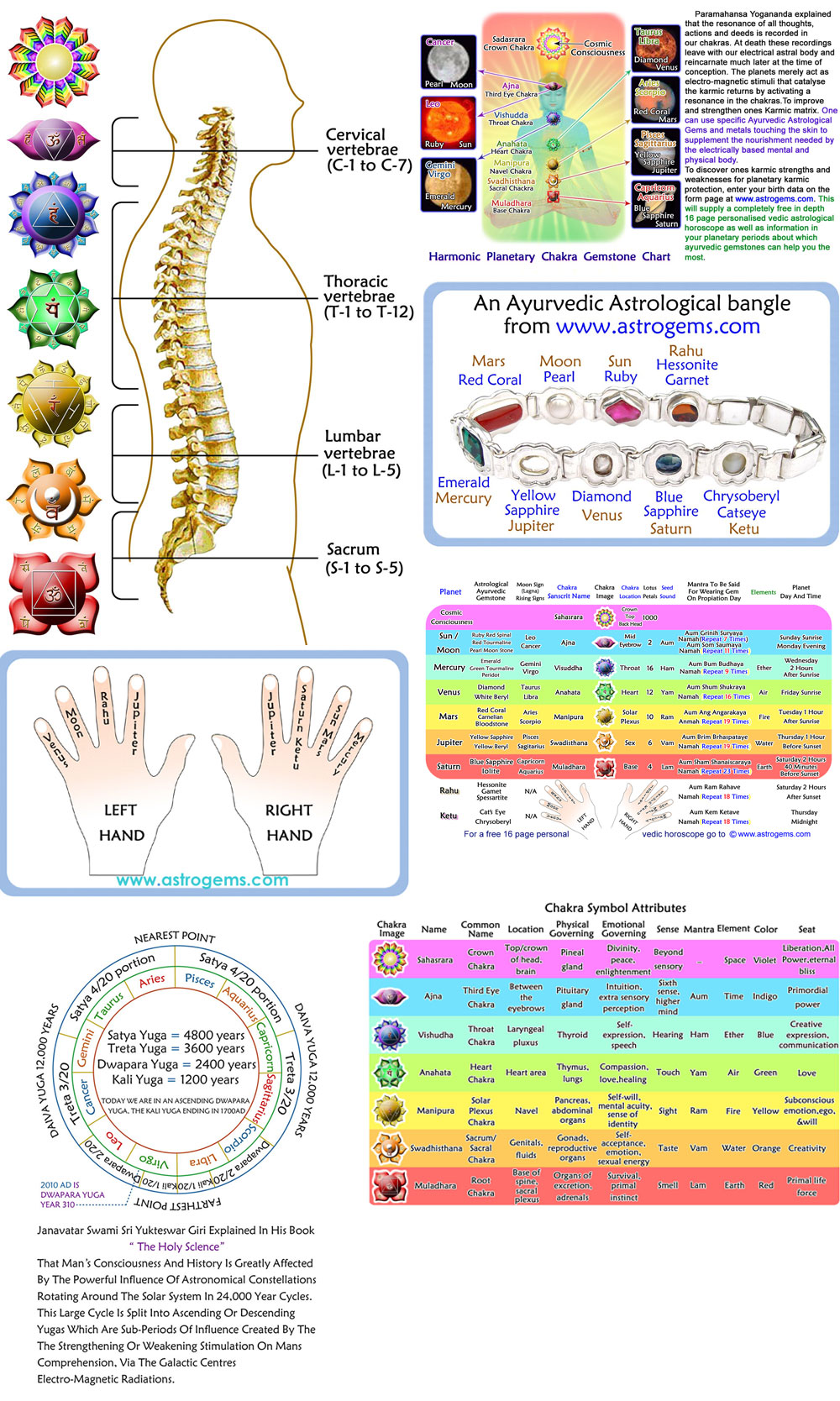

"Just as a house can be fitted with a copper rod to

absorb the shock of lightning, so the bodily temple can be

benefited by various protective measures. Ages ago our yogis

discovered that pure metals emit an astral light which is

powerfully counteractive to negative pulls of the planets.

Subtle electrical and magnetic radiations are constantly circulating

in the universe; when a man's body is being aided, he does

not know it; when it is being disintegrated, he is still in

ignorance. Can he do anything about it?

"This problem received attention from our rishis; they

found helpful not only a combination of metals, but also of

plants and—most effective of all—faultless jewels

of not less than two carats. The preventive uses of astrology

have seldom been seriously studied outside of India. One little-known

fact is that the proper jewels, metals, or plant preparations

are valueless unless the required weight is secured, and unless

these remedial agents are worn next to the skin."

"Sir, of course I shall take your advice and get a bangle.

I am intrigued at the thought of outwitting a planet!"

"For general purposes I counsel the use of an armlet

made of gold, silver, and copper. But for a specific purpose

I want you to get one of silver and lead." Sri Yukteswar

added careful directions.

"Guruji, what 'specific purpose' do you mean?"

"The stars are about to take an unfriendly interest

in you, Mukunda. Fear not; you shall be protected. In about

a month your liver will cause you much trouble. The illness

is scheduled to last for six months, but your use of an astrological

armlet will shorten the period to twenty-four days."

I sought out a jeweler the next day, and was soon wearing

the bangle. My health was excellent; Master's prediction slipped

from my mind. He left Serampore to visit Benares. Thirty days

after our conversation, I felt a sudden pain in the region

of my liver. The following weeks were a nightmare of excruciating

pain. Reluctant to disturb my guru, I thought I would bravely

endure my trial alone.

But twenty-three days of torture weakened my resolution;

I entrained for Benares. There Sri Yukteswar greeted me with

unusual warmth, but gave me no opportunity to tell him my

woes in private. Many devotees visited Master that day, just

for a darshan. 2 Ill and neglected, I sat in a corner. It

was not until after the evening meal that all guests had departed.

My guru summoned me to the octagonal balcony of the house.

"You must have come about your liver disorder."

Sri Yukteswar's gaze was averted; he walked to and fro, occasionally

intercepting the moonlight. "Let me see; you have been

ailing for twenty-four days, haven't you?"

"Yes, sir."

"Please do the stomach exercise I have taught you."

"If you knew the extent of my suffering, Master, you

would not ask me to exercise." Nevertheless I made a

feeble attempt to obey him.

"You say you have pain; I say you have none. How can

such contradictions exist?" My guru looked at me inquiringly.

I was dazed and then overcome with joyful relief. No longer

could I feel the continuous torment that had kept me nearly

sleepless for weeks; at Sri Yukteswar's words the agony vanished

as though it had never been.

I started to kneel at his feet in gratitude, but he quickly

prevented me.

"Don't be childish. Get up and enjoy the beauty of the

moon over the Ganges." But Master's eyes were twinkling

happily as I stood in silence beside him. I understood by

his attitude that he wanted me to feel that not he, but God,

had been the Healer.

I wear even now the heavy silver and lead bangle, a memento

of that day—long-past, ever-cherished—when I found

anew that I was living with a personage indeed superhuman.

On later occasions, when I brought my friends to Sri Yukteswar

for healing, he invariably recommended jewels or the bangle,

extolling their use as an act of astrological wisdom.

I had been prejudiced against astrology from my childhood,

partly because I observed that many people are sequaciously

attached to it, and partly because of a prediction made by

our family astrologer: "You will marry three times, being

twice a widower." I brooded over the matter, feeling

like a goat awaiting sacrifice before the temple of triple

matrimony.

"You may as well be resigned to your fate," my

brother Ananta had remarked. "Your written horoscope

has correctly stated that you would fly from home toward the

Himalayas during your early years, but would be forcibly returned.

The forecast of your marriages is also bound to be true."

A clear intuition came to me one night that the prophecy

was wholly false. I set fire to the horoscope scroll, placing

the ashes in a paper bag on which I wrote: "Seeds of

past karma cannot germinate if they are roasted in the divine

fires of wisdom." I put the bag in a conspicuous spot;

Ananta immediately read my defiant comment.

"You cannot destroy truth as easily as you have burnt

this paper scroll." My brother laughed scornfully.

It is a fact that on three occasions before I reached manhood,

my family tried to arrange my betrothal. Each time I refused

to fall in with the plans,3 knowing that my love for God was

more overwhelming than any astrological persuasion from the

past.

"The deeper the self-realization of a man, the more

he influences the whole universe by his subtle spiritual vibrations,

and the less he himself is affected by the phenomenal flux."

These words of Master's often returned inspiringly to my mind.

Occasionally I told astrologers to select my worst periods,

according to planetary indications, and I would still accomplish

whatever task I set myself. It is true that my success at

such times has been accompanied by extraordinary difficulties.

But my conviction has always been justified: faith in the

divine protection, and the right use of man's God-given will,

are forces formidable beyond any the "inverted bowl"

can muster.

The starry inscription at one's birth, I came to understand,

is not that man is a puppet of his past. Its message is rather

a prod to pride; the very heavens seek to arouse man's determination

to be free from every limitation. God created each man as

a soul, dowered with individuality, hence essential to the

universal structure, whether in the temporary role of pillar

or parasite. His freedom is final and immediate, if he so

wills; it depends not on outer but inner victories.

Sri Yukteswar discovered the mathematical application

On my return from Japan, I learned that during my absence Nalini had been stricken with typhoid fever. I rushed to her home, and was aghast to find her reduced to a mere skeleton. She was in a coma.

"Before her mind became confused by illness," my brother-in-law told me, "she often said: 'If brother Mukunda were here, I would not be faring thus.'" He added despairingly, "The other doctors and myself see no hope. Blood dysentery has set in, after her long bout with typhoid."

I began to move heaven and earth with my prayers. Engaging an Anglo-Indian nurse, who gave me full cooperation, I applied to my sister various yoga techniques of healing. The blood dysentery disappeared.

For a free high resolution copy of this image

of Swami Sri Yukteswar Click Here.

But Dr. Bose shook his head mournfully. "She simply has no more blood left to shed."

"She will recover," I replied stoutly. "In seven days her fever will be gone."

A week later I was thrilled to see Nalini open her eyes and gaze at me with loving recognition. From that day her recovery was swift. Although she regained her usual weight, she bore one sad scar of her nearly fatal illness: her legs were paralyzed. Indian and English specialists pronounced her a hopeless cripple.

The incessant war for her life which I had waged by prayer had exhausted me. I went to Serampore to ask Sri Yukteswar's help. His eyes expressed deep sympathy as I told him of Nalini's plight.

"Your sister's legs will be normal at the end of one month." He added, "Let her wear, next to her skin, a band with an unperforated two-carat pearl, held on by a clasp."

I prostrated myself at his feet with joyful relief.

"Sir, you are a master; your word of her recovery is enough But if you insist I shall immediately get her a pearl."

My guru nodded. "Yes, do that." He went on to correctly describe the physical and mental characteristics of Nalini, whom he had never seen.

"Sir," I inquired, "is this an astrological analysis? You do not know her birth day or hour."

Sri Yukteswar smiled. "There is a deeper astrology, not dependent on the testimony of calendars and clocks. Each man is a part of the Creator, or Cosmic Man; he has a heavenly body as well as one of earth. The human eye sees the physical form, but the inward eye penetrates more profoundly, even to the universal pattern of which each man is an integral and individual part."

I returned to Calcutta and purchased a pearl for Nalini. A month later, her paralyzed legs were completely healed.

Sister asked me to convey her heartfelt gratitude to my guru. He listened to her message in silence. But as I was taking my leave, he made a pregnant comment.

"Your sister has been told by many doctors that she can never bear children. Assure her that in a few years she will give birth to two daughters."

Some years later, to Nalini's joy, she bore a girl, followed in a few years by another daughter.

"Your master has blessed our home, our entire family," my sister said. "The presence of such a man is a sanctification on the whole of India. Dear brother, please tell Sri Yukteswarji that, through you, I humbly count myself as one of his KRIYA YOGA disciples."

The

first part of Chapter 17

Sasi and the Three Sapphires

"Because

you and my son think so highly of Swami Sri Yukteswar, I will

take a look at him." The tone of voice used by Dr. Narayan

Chunder Roy implied that he was humoring the whim of half-wits.

I concealed my indignation, in the best traditions of the

proselyter.

My companion, a veterinary surgeon, was a confirmed agnostic.

His young son Santosh had implored me to take an interest

in his father. So far my invaluable aid had been a bit on

the invisible  side. side.

Dr. Roy accompanied me the following day to the Serampore

hermitage. After Master had granted him a brief interview,

marked for the most part by stoic silence on both sides, the

visitor brusquely departed.

"Why bring a dead man to the ashram?" Sri Yukteswar

looked at me inquiringly as soon as the door had closed on

the Calcutta skeptic.

"Sir! The doctor is very much alive!"

"But in a short time he will be dead."

I was shocked. "Sir, this will be a terrible blow to

his son. Santosh yet hopes for time to change his father's

materialistic views. I beseech you, Master, to help the man."

"Very well; for your sake." My guru's face was

impassive. "The proud horse doctor is far gone in diabetes,

although he does not know it. In fifteen days he will take

to his bed. The physicians will give him up for lost; his

natural time to leave this earth is six weeks from today.

Due to your intercession, however, on that date he will recover.

But there is one condition. You must get him to wear an astrological

bangle; he will doubtless object as violently as one of his

horses before an operation!" Master chuckled.

After a silence, during which I wondered how Santosh and

I could best employ the arts of cajolery on the recalcitrant

doctor, Sri Yukteswar made further disclosures.

"As soon as the man gets well, advise him not to eat

meat. He will not heed this counsel, however, and in six months,

just as he is feeling at his best, he will drop dead. Even

that six-month extension of life is granted him only because

of your plea."

The following day I suggested to Santosh that he order an

armlet at the jeweler's. It was ready in a week, but Dr. Roy

refused to put it on.

"I am in the best of health. You will never impress

me with these astrological superstitions." The doctor

glanced at me belligerently.

I recalled with amusement that Master had justifiably compared

the man to a balky horse. Another seven days passed; the doctor,

suddenly ill, meekly consented to wear the bangle. Two weeks

later the physician in attendance told me that his patient's

case was hopeless. He supplied harrowing details of the ravages

inflicted by diabetes.

I shook my head. "My guru has said that, after a sickness

lasting one month, Dr. Roy will be well."

The physician stared at me incredulously. But he sought me

out a fortnight later, with an apologetic air.

"Dr. Roy has made a complete recovery!" he exclaimed.

"It is the most amazing case in my experience. Never

before have I seen a dying man show such an inexplicable comeback.

Your guru must indeed be a healing prophet!"

After one interview with Dr. Roy, during which I repeated

Sri Yukteswar's advice about a meatless diet, I did not see

the man again for six months. He stopped for a chat one evening

as I sat on the piazza of my family home on Gurpar Road.

"Tell your teacher that by eating meat frequently, I

have wholly regained my strength. His unscientific ideas on

diet have not influenced me." It was true that Dr. Roy

looked a picture of health.

But the next day Santosh came running to me from his home

on the next block. "This morning Father dropped dead!"

This case was one of my strangest experiences with Master.

He healed the rebellious veterinary surgeon in spite of his

disbelief, and extended the man's natural term on earth by

six months, just because of my earnest supplication. Sri Yukteswar

was boundless in his kindness when confronted by the urgent

prayer of a devotee.

It was my proudest privilege to bring college friends to

meet my guru. Many of them would lay aside—at least

in the ashram!—their fashionable academic cloak of religious

skepticism.

One of my friends, Sasi, spent a number of happy week ends

in Serampore. Master became immensely fond of the boy, and

lamented that his private life was wild and disorderly.

"Sasi, unless you reform, one year hence you will be

dangerously ill." Sri Yukteswar gazed at my friend with

affectionate exasperation. "Mukunda is the witness: don't

say later that I didn't warn you."

Sasi laughed. "Master, I will leave it to you to interest

a sweet charity of cosmos in my own sad case! My spirit is

willing but my will is weak. You are my only savior on earth;

I believe in nothing else."

"At least you should wear a two-carat blue sapphire.

It will help you."

"I can't afford one. Anyhow, dear guruji, if trouble

comes, I fully believe you will protect me."

"In a year you will bring three sapphires," Sri

Yukteswar replied cryptically. "They will be of no use

then."

Variations on this conversation took place regularly. "I

can't reform!" Sasi would say in comical despair. "And

my trust in you, Master, is more precious to me than any stone!"

A year later I was visiting my guru at the Calcutta home

of his disciple, Naren Babu. About ten o'clock in the morning,

as Sri Yukteswar and I were sitting quietly in the second-floor

parlor, I heard the front door open. Master straightened stiffly.

"It is that Sasi," he remarked gravely. "The

year is now up; both his lungs are gone. He has ignored my

counsel; tell him I don't want to see him."

Half stunned by Sri Yukteswar's sternness, I raced down the

stairway. Sasi was ascending.

"O Mukunda! I do hope Master is here; I had a hunch

he might be."

"Yes, but he doesn't wish to be disturbed."

Sasi burst into tears and brushed past me. He threw himself

at Sri Yukteswar's feet, placing there three beautiful sapphires.

"Omniscient guru, the doctors say I have galloping tuberculosis!

They give me no longer than three more months! I humbly implore

your aid; I know you can heal me!"

"Isn't it a bit late now to be worrying over your life?

Depart with your jewels; their time of usefulness is past."

Master then sat sphinxlike in an unrelenting silence, punctuated

by the boy's sobs for mercy.

|

|

An intuitive conviction came to me that Sri Yukteswar was

merely testing the depth of Sasi's faith in the divine healing

power. I was not surprised a tense hour later when Master

turned a sympathetic gaze on my prostrate friend.

"Get up, Sasi; what a commotion you make in other people's

houses! Return your sapphires to the jeweler's; they are an

unnecessary expense now. But get an astrological bangle and

wear it. Fear not; in a few weeks you shall be well."

Sasi's smile illumined his tear-marred face like sudden sun

over a sodden landscape. "Beloved guru, shall I take

the medicines prescribed by the doctors?"

Sri Yukteswar's glance was longanimous. "Just as you

wish—drink them or discard them; it does not matter.

It is more possible for the sun and moon to interchange their

positions than for you to die of tuberculosis." He added

abruptly, "Go now, before I change my mind!"

With an agitated bow, my friend hastily departed. I visited

him several times during the next few weeks, and was aghast

to find his condition increasingly worse.

"Sasi cannot last through the night." These words

from his physician, and the spectacle of my friend, now reduced

almost to a skeleton, sent me posthaste to Serampore. My guru

listened coldly to my tearful report.

"Why do you come here to bother me? You have already

heard me assure Sasi of his recovery."

I bowed before him in great awe, and retreated to the door.

Sri Yukteswar said no parting word, but sank into silence,

his unwinking eyes half-open, their vision fled to another

world.

I returned at once to Sasi's home in Calcutta. With astonishment

I found my friend sitting up, drinking milk.

"O Mukunda! What a miracle! Four hours ago I felt Master's

presence in the room; my terrible symptoms immediately disappeared.

I feel that through his grace I am entirely well."

In a few weeks Sasi was stouter and in better health than

ever before.1 But his singular reaction to his healing had

an ungrateful tinge: he seldom visited Sri Yukteswar again!

My friend told me one day that he so deeply regretted his

previous mode of life that he was ashamed to face Master.

I could only conclude that Sasi's illness had had the contrasting

effect of stiffening his will and impairing his manners. |

| ( This image is not in the Autobiography of a Yogi and is a color enhanced photo of Paramahansa Yogananda on the beach copyright www.astrogems.com) |

Page 1 | Page 2

|

Excerpts

from "Autobiography of a Yogi"

Excerpts

from "Autobiography of a Yogi"

side.

side.